How to talk to a friend about sexual abuse

Patrick talks to John about the sexual abuse he endured as a child. They discuss the best ways to talk to friends about childhood sexual abuse, and Patrick shares his personal journey from sexual abuse to healing.

I’m here to tell you this is not like any other coffee morning I’ve done before.

So it’s a great we’ve been able to find time to have a chat because I’ve got no experience of sexual abuse. I’ve got no idea about it, really. So I’m hoping that in talking to you, I can somehow be helpful to guys that have been through it and maybe get some ideas of what to say, what not to say and how to be supportive.

I just think you can say anything you like as long as it’s honest. The thing that survivors don’t like is being patronised. Nobody wants to be said, ‘there there’ – ‘I’m so sorry’, you know, because actually, we’re all human beings and most of us, simply to have survived, we’ve got something going on in here, which is quite positive and quite determined. And most of the survivors I’ve met are actually very courageous and resourceful and enterprising, and I learn a lot from them and maybe they learn a bit from me.

Of course, there are others who I never meet, and there are some who fall by the wayside. Whatever that may mean, who either go into addiction or worse. I mean, nobody knows how many commit suicide. We don’t know. But an awful lot of us don’t. A lot of us battle through – find a way through. Find a way to survive and find a way to lead more or less ordinary lives, whatever that means.

Personally, I don’t like the words like normal and ordinary, I don’t think they mean anything, But do you find then if you start talking, do you not find, people, do they shut down?

Are they interested or like… It’s a bit of a showstopper. In terms of conversations.

Well I’m careful, I think, I’m careful who I talk to. I mean, I don’t I wouldn’t strike up a conversation with a stranger saying, Oh, by the way, “I’m a survivor of childhood sexual abuse”. It’s not exactly the best opener of a conversation. I suppose quite often you can sense whether a person is interested because everybody in their life has traumas. We all have wounds from when we were young, that we have to recover from. Some of them You know, for some of us it’s sexual abuse, for other people it might be childhood illnesses, it might be parents getting divorced. It might be one parent or the other in prison.

It could be any… all sorts of things are traumas and sexual abuse is just a particularly acute form of trauma, a wound that hits a child when he or she is very young and it can have a very lasting effect on their life.

But I’m not an expert on child protection. I’m an expert on me and my recovery and some of the other people I know, some of whom I want to say are not, were not children when they were abused. I mean, I know a lot of survivors who were in their teens and even adults, and it can be very similar, particularly

I mean, maybe the grooming is less subtle. Maybe it’s a drink being spiked and then somebody being raped, for example. And quite often that person might feel it’s their fault for allowing themselves to be taken in enough to have their drink spiked, which is not true if somebody is sexually attacked, the attacker is the villain. Nobody else is to blame. Whatever the circumstances, forced sexual activity is the crime. I think the most important thing of all is whether the child or the young adult is able to talk about it afterwards.

I think if I had had somebody… I was abused by my primary school teacher when I was nine and ten years old in a state primary school at Gravesend in Kent, my mother happened to think that that teacher was a terrific teacher because he persuaded her that he was, by telling her that I was his star pupil and by making me top of the class. I think if I had been able to say to my mother,

Do you know what he’s doing to me? I probably would not have been so damaged. I think the communication, the talking about it afterwards is actually every bit as important as actually what’s going on there.

Having not been through it myself, what is it to stops people saying? what stops a child saying ?

Oh, well, I think the one word is ‘shame’.

Quite often the abuser or the perpetrator, quite often the abuser will swear you to secrecy. ‘Please don’t tell anybody if you tell anybody, I’ll get into trouble.’ ‘This is our secret.’ ‘This is just between you and me. ”You know how much I like you, how much I love you.’

‘It’s only it’s just me showing I love you.’ I also think that in psychological terms, the child can’t bear that the adult is bad because if the adult is bad, then the child is alone and on his own and on his or her own. And that is unbearable.

So the child takes on the badness, so I become bad. That’s the shame I become not a proper person. I become defective. In my case, I thought I was hideously ugly. Mostly because my teacher suddenly stopped abusing me when I got to age ten and he went onto a younger model. He rejected me, he said, Bye bye, off you go. And I felt totally bereft. Not that I enjoyed what he was doing.

I hated what he was doing, but I liked the attention and I liked being top of the class, and I liked the fact that my mother thought… he used to come to our house, as well as abusing me in the classroom because my mother thought it was a really good teacher. So of course, I wanted to be that perfect little boy.

But you see for me, and I already feel myself doing it, my blood’s rising. I’m starting to feel violent now. Is that not me stealing your pain?

No. That’s you having a totally understandable human reaction.

I get full of rage.

I think most survivors have to deal with anger at one point or another because something, the core inside you has been wounded and of course, you’re going to get angry.

It’s the important thing to find ways of expressing that anger, and that’s not always easy.

As for prevalence, they say that one in six males, one in three females, endure unwanted sexual activity. Now some of that is peer on peer. Of course it is, but quite a lot of it is adult to young person.

Why do people do it?

Oh, you tell me. It’s a big question, and I’m certainly not the expert to answer that. What I do know is that it’s not always about sexual gratification. I think it’s about lots of other things, particularly power, whether that is a boss being inappropriate with an employee or a coach being inappropriate with a team member or lots of other human situations.

People can be vulnerable and lonely and that can make and do things that they shouldn’t do. I think the myth of the man in the coat at the school gates, that is a myth, and that’s got to be dispelled. It’s just just as likely to be the headmaster in the school ‘It couldn’t be him. He’s your uncle, for goodness sake.’ That’s what people say. ‘She’s your cousin.’ She’s not going to touch you. How dare you say that about your cousin? Sometimes the abuse is at home, and quite often it may be from a woman. Men are abused by women. This is a big taboo now. I think Mankind says that among the men who come to them, 34% say they have been abused by women. And it takes quite a lot of courage for a man to say I’ve been abused by a woman. But it happens, and quite a lot of those women are the mothers or the older sisters. Women abusers are a taboo still in our society

Because I knew I was going to be talking to you today I’ve been speaking to friends about it, and just this morning, a mate of mine said to me that he was abused by his mum and I had no idea, he’s never mentioned this before.

Of course he’s never mentioned it.

So I’m like, But we’re friends. Why couldn’t you have told me this years ago? But I don’t want to say that to him, but now I’m thinking ‘What have I done that hasn’t made me appear open enough for him to feel able to tell me’?

You haven’t done anything. And you are obviously open enough for him to have told you now. And he told you when he was ready to tell you, it maybe took him 20 years to tell himself and admit it to himself. Nobody wants to say that about their mother. But see again… That makes him an orphan.

Yeah, I do see that

If his mother is a bad woman, that means he hasn’t got a mother.

It just seems to me that it’s because I feel like it’s a bit of a minefield, I don’t want to say the wrong thing or do or be part of the problem. And a great way of not saying the wrong thing is to say nothing.

That has to be your decision. But I mean, I much prefer it if people ask me straightforward questions. But I, you know, I’m older. I’ve been dealing with this stuff for a long time. By and large, I’m much more balanced than I used to be. I’m not embarrassed by questions anymore. But you have to ask me anything today that I found offensive at all.

I’m very happy to answer those questions. I think you have to judge where a person is on their recovery journey.

So in terms of the healing then… how do you start the process? How did you begin to kind of, not get over it, but…?

Talking, talking. You have to talk about it. Abuse happens in secret. Recovery happens in community. You have to talk about it.

You have to tell somebody you trust. That might be a member of your family. If it’s somebody you really trust, but you have to pick them carefully. Or it might be a therapist, or it might be your GP or it might just be a really good friend. But until you start to talk about it and tell the truth, you’re not going to get anywhere. Telling the truth is so important.

Abuse is a lie. It’s an enormous lie because it’s pretending affection – is pretending trust while actually taking trust away. And the only way you can heal a lie is by telling the truth. And once you’ve told it to one person, then you can start to tell it to other people. And the most useful people to tell it to are other people who have been through the same situation. Join a group of other survivors or other rape victims.

Perhaps if you’re older, it can be a magical experience because suddenly you realise you’re not alone and somebody says something across the circle and you think, ‘Oh my God, I’m just like that’, or ‘I believe’ or ‘I wasn’t quite like that, but sort of not, not dissimilar’. And that can be incredibly healing.

A big step for me was realising that it’s all about my body. I thought, of course, because I’m a kind of intelligent kind of person that I could sort it all out in my head, I’ll get it all sorted out. But abuse happens in the body. It’s a crime against the body and it’s held…the effects are held in the body. And I think at some point or other in your healing, you have to do some work on your body. It might be as simple as massage, it might be…In my case, I didn’t allow anybody to touch me physically for 15 years, from the age ten to 25 part. From the peck on the cheek or a handshake. For me to be hugged was impossible. I couldn’t do it.

And gradually learning to trust that people might want to hug me or might want to get into bed with me in a way that was trusting and loving that took me a very long time to learn.

What else can survivors do to start that journey?

Well, I think they can help themselves by looking as widely as possible for solutions and things to help them, for example, www.1in6.uk. The website has amazing resources on it. It has extraordinary animations, it has films about trauma. It has all sorts of information that will give survivors ideas of what might be right for them because this is not a one size fits all. It’s not an exact science.

People have to find their own way through. You can go and find other groups. You can find books.There are some really good books out there. You can talk to other survivors and find ways they’ve done it.

I have a friend. and he said what made him recover was finding table-tennis because he suddenly found there’s something about hitting the racket really hard that was really helpful to him.

It got his anger out and then laughing about things. LAUGHTER is very important. You know, that bit of humor is really good.

How do you come to terms with it?

I think the answer is slowly and with as much help as you can get. I believe very strongly that recovery is possible. I think it’s a slow process. I think it’s two steps forward, one step back. And I think talking about it is the most important thing of all.

You can’t keep it secret… I think abuse happens in secret. Recovery has to happen in community.You can only really recover talking to other people. That might be by starting to talk to a therapist or going to a group of other survivors. For me, that was the most incredible thing. But the first time I met a group of other men who’d been abused at all different ages, some as kids, some in their teens, some had been raped in their twenties. Just to meet them and hear their experiences, not so much what had happened to them, but how they had coped with it and what the effects had been was incredibly valuable and very healing.

But then so if I… I want to be part of the recovery, what do I do? Are there things people say to you …?

You’re doing it now. You know what you’re doing, which is so fantastic? You’re taking the subject seriously, and, you know, that’s what moves me. Just you asking me these straightforward questions without holding anything back and without patronising me, you’ve never once said, ‘Oh Patrick, you poor thing’, you haven’t said that you meet me with great respect. You meet me as an equal. I happen to have had a rather unpleasant experience, which I’ve been coping with and resolving for a long time in my adult life.

And you’re understanding that I’m trying to understand it.

Do you know what? So am I. Trying to understand it. The one thing I do want to say is what what we talk about is called the myth of the vampire.

The idea that if a man is abused, he goes on and becomes an abuser. This is not. This is simply not true. A very large number of men who abuse have themselves been abused. But the opposite isn’t true.

So it’s not a natural progression?

No, no. I mean, there are hundreds, literally hundreds of survivors, both men and women who would no more dream of abusing a child they just, it just wouldn’t enter their thinking. On the contrary, if anything, they would be either slightly wary of children or very protective or passionate about, you know, resolving the situation that we have in society at the moment.

You do survivors a great disservice when you think that they are going to abuse because they’re not. You might as well say any woman who’s raped is going to become a rapist. It doesn’t work like that.

Do you think there’s more stigma for male victims of abuse?

Yes. Yes I do. I don’t think it’s better or worse than female abuse. I just think it’s different. I think that men are supposed to be strong. Men are not supposed to be vulnerable. Men are not supposed to talk about their emotions and their feelings so that I think it can be harder. And I also think there is a danger with men that if you are abused, people automatically assume you’re gay or they will say, ‘Oh, you’re a sissy, you’re soft, you shouldn’t have let it happen’.

But would there be things that people have said to you that just completely inappropriate or unhelpful? that I would hope not to say myself?

Well, the thing that people say, which irritates me, is when people say, ‘but this happened to you years ago when you were a child, you must have got over it by now’. And that really misses the point. First of all, because when you were abused, you suppress it. You don’t want to talk about it. You want to pretend it didn’t happen or you think it’s your fault.

So you just sit on it. And I waited 25 years before I told anybody. And I think the other thing is, if people say to me, this happened years ago, I say yes and I’ve been dealing with the consequences for all those years.

So don’t give me that, frankly, that crap about you should have got over it years ago. It’s missing the point.

So, how do you think it’s affected you?

Mm hmm. How long have you got? Oh, how has it affected me? The shame is the big one. It’s the shame. It’s feeling for me, the worst was feeling I was ugly, feeling I wasn’t a proper man. Having a completely skewed version… view of sex. Relationships were very difficult. Trusting anybody was very difficult. I was very hyper vigilant because when something is so scary, you know, every time a teacher comes, you think what are they going to do? what are they going to do? and that kind of hyper vigilance and being careful around people

It’s funny, because people often say, Oh he’s a very disruptive child in class, He might have been abused. And actually, I was the opposite. I was the good child. I was the perfectionist. I was the academic achiever. I thought if I do well enough at school, people will forgive me for being the ‘bad’ person that I am underneath. At university, I used to hit the booze quite a lot, but then lots of students do that. I became very much a workaholic. I retreated into my imagination. I went into the theatre because characters, imaginary characters were much easier to do deal with in real people. I was a virgin until I was 26.

As a gay man, that was quite unusual because I was so scared of people, and I also thought that I was so ugly nobody could possibly want me. But those all those effects I have worked on in my therapy. They have receded a little bit. It affects lots of people in different ways. I do know depression, sadness for what’s missed. Grief for what has been missed. When you realise what’s been taken away, I think that’s quite a big one. And anger, which is the opposite of grief.

Never underestimate the courage it takes to begin the process of recovery.

So how how should we refer to you? Are you…Are you victims? Are you survivors? Are you…? What are you?

You can call me by my name. I think victim is an unfortunate word. I suppose as soon as you start to recover from it, you are, in a sense, a survivor. And I think there’s a certain power in that. I also know there are lots of people who don’t like the word survivor because I think it I think it can be a slightly stigmatizing word. And I think one of the important things about identity, which I say to myself, is this is what was done to me. It is not who I am.

I am more than the sexual abuse that was done to me. My identity is infinitely wider than that. And I think to classify somebody just as a survivor of abuse is a bit narrow because we’re all rich, complicated, wonderful human beings.

And if you’re not sure, ask the person. I mean, I would never choose to be called a survivor. I’m not offended if you call me a survivor. But I’d rather you just call me Patrick.

I mean, is there anything you can think of that I could say to my mate? That would be helpful.

Good on you. Say to him. Good on you. Thank you for telling me that. God, that took guts to tell me that, I really appreciate that.

Is there anything I could advise him to do or anything. I can suggest that’s going to help?

Ask him what he thinks, in his heart of hearts, he needs to do next? And it might be that he needs to go and find professional help and realise that that decision is a really big one and give him what support he can have. And tell him, that to seek professional help is a sign of his strength, not of his weakness. Is it something that you can do to rebuild your life. You can get on with it?

How does it work?

I would say I learned to live with it. It’s no longer the demon on the driving wheel. It’s maybe on the other side of the dual carriageway running up and down the pavement, and occasionally it will zoom across and try and attack me if I get tired or if I get stressed, or if I’m in a difficult situation. But I realise ultimately that life is very possible and indeed can be very enjoyable. And people are not frightening, because I think that the biggest thing. Well, I think the biggest effect is shame and shame means I feel it was my fault or I feel I am bad, or I feel I’m not a proper person. I feel I’m not a proper man, and therefore nobody will love me and I’m not good enough.

That’s the thing I have to overcome more than anything, and I do that by letting people tell me it’s not true. And by trying to listen to them and letting them tell me again and letting people whom I trust and realising that being asked to do this conversation with you today must mean I’m alright.

I think you’re all right.

Thank you. And I believe you. I believe you. And that’s the most important thing, because if I can believe I’m all right, then anything is possible and I can make my life be whatever I want it to be.

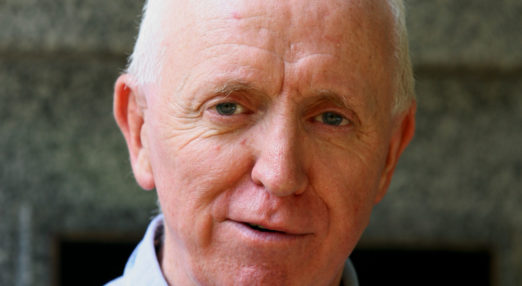

Patrick Sandford is a playwright and director and is a survivor of childhood sexual abuse.

He is a trustee of Mankind UK and works with a wide range of sexual abuse support organisations to advocate for policy change around prevention, healing and justice for all survivors.

He is on the Advisory Group which leads the delivery of 1in6.uk.

John Ryan is a comedian, trainer and ally to male survivors. He works with health charities to use comedy to share information and encourage men in particular to have conversations about mental health.

He is keen to learn how to become a good ally to his friends who have been sexually assaulted or abused.